Rethinking Woman Suffrage, 100 Years In

August 26, 2020 marks the centennial of the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” Simple wording. Enormous impact. Complicated history.

This discussion is divided into five parts. Part 1: context provided by the Constitution and the early suffrage movement in the United States. Part 2: events in Texas during this time. Part 3: women of color in the Texas suffrage story. Part 4: White women in the Texas suffrage story. Part 5: the dangerous state of the vote today.

Part 1: The Constitution and the U.S. Woman Suffrage Movement

Here in the 21st century, we take for granted the link between citizenship and voting. The 19th Amendment is a legality that many of us consider a watertight guarantee.

That was not true in the new Constitution, however. It could be quite vague. There was no definition of citizenship and no link at all between citizenship and voting. In fact, in 1787, when the Constitution was written, people thought in terms of “laws of nature” that taught them that women, children, and Black people were not equal to White men, who were the first people allowed to vote here. They were the people who counted, so to speak.

And the people who didn’t count knew it.

Like women. Remember Abigail Adams? Her demand of her husband, John, to “Remember the Ladies” is well known. Less known is her followup warning: “or we will foment a rebellion.” John’s reply? “I prefer my masculine systems.” And then he muttered something about women as bothersome petticoats.

African Americans also understood they did not count. After all, slavery was 170 years old by then. Abolition was high on their list of reforms. A lot of the people who supported abolition were White women, because they identified with not having equal rights.

By 1848, enough abolitionists and feminists, White and Black, believed in equal rights for all women that they called a convention in Seneca Falls, New York and, copying the Declaration of Independence, issued a Declaration of Sentiments stating that all men and women were equal and that there were several rights that all women deserved, regardless of the color of their skin. One of those rights was the vote. Bi-racial groups of abolitionists and feminists cooperated through the Civil War to make all those reforms a reality.

The two biggest names in that coalition were Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the former slave Frederick Douglass. After the Civil War was over, they got a lot of what they wanted:

The 13th Amendment (1865) outlawed slavery.

The 14th Amendment (1868) defined citizenship as anyone born or naturalized in the U.S. And then it made a mention that male citizens could vote. That was the first time the word “male” appeared in the Constitution: linked to the vote. This was not an assertion that only men could vote. Like the laws of nature, this was an underlying assumption at last made clear, but as an afterthought. Like a forgotten note slipped under a door. But at least the 14th Amendment did clarify that a huge swath of people were citizens, regardless of color or sex.

And then the 15th Amendment (1870), in the unfortunate style of the Constitution, declared vaguely, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” So, technically speaking, to a lot of people, this could have meant any citizen, male or female.

In fact, a lot of women thought that they could now vote, since they and formerly enslaved people were now officially citizens. Many women tried and were turned away. Susan B. Anthony was one of them, and she was arrested for it. Because there were several law suits over this, the Supreme Court declared a few years later that just because women were citizens, that did not mean they could vote. After all, the 15th Amendment had not include the word “sex” as well as “race” among those who qualified.

When some women realized that African American men had been granted the vote but that White women had not, that bi-racial coalition at Seneca Falls blew up. In 1869 it split into two competing groups that focused entirely on suffrage.

Frederick Douglass’s group supported both the 15th Amendment and “universal” suffrage for men and women, Black and White. But Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s group supported “educated woman suffrage” for White women only. She thought the 15th Amendment was an “abomination” that created friction between “educated, refined women,” which was code for White, and the “lower orders of men,” which was code for Black. Stanton and Susan B. Anthony would later lead the nationwide suffrage movement and put those attitudes into operation.

Part 2: What about Texas?

For comparison’s sake, Texas in 1848, at the time of the Seneca Falls Convention, was a fairly new state. Texas had come into existence in a series of steps similar to those that the U.S. had taken. What became Texas started around 1820 when slaveholding American southerners moved to Mexico as colonists to establish their right to slavery without restriction. Some historians have suggested they wanted to create “an empire for slavery.” But Mexico would not legalize slavery, so the colonists rebelled and formed their own independent Republic of Texas, where slavery was legal. When that did not work economically, the Republic became a state. A slave holding state.

As both a Republic and then as a state, Texas wrote nearly identical constitutions declaring that slavery was legal, that only Anglos could be citizens, and that only White men could vote. Their desires were clear. About a decade later, Texas seceded from the United States to join the Confederacy of southern states that hoped to establish a new country in which slavery was legal. They lost the Civil War that resulted.

During Reconstruction, Republican Unionists, starting with the U.S. Army, moved into the former Confederate states to initiate the reform of southern states into places where civil rights existed for all citizens, regardless of color. Once again, Texas had to write a new constitution, this time to align itself with the U.S. to be readmitted to the Union. Reform, particularly enfranchisement, was in the air. At the first constitutional convention, in 1868, one delegate suggested that women should have the right to vote. That proposal failed. In fact, woman suffrage proposals would be voted on nine more times between then and 1918, when it finally passed. All nine of them failed.

During Reconstruction, most Whites in Texas had supported slavery and the Confederacy, and they were Democrats. They did not like Reconstruction. They did not like the Republicans’ 13th, 14th, or 15th Amendments either. They did not want Black men to vote, and they were never going to allow White women to vote if Black men could.

White southern Democrats didn’t want reconstruction. They wanted the restoration of the hierarchical society they had controlled before the Civil War. In Texas, White Democrats considered themselves “redeemers” who were determined to save Texas from Republican reform. The 13th Amendment, for example, declared slavery illegal, but it also included an enormous loophole that southerners noticed: Slavery and involuntary servitude could be re-instituted for criminal behavior. So redeemers created Black Codes, laws that made illegal almost every form of activity in which African Americans and former slaves engaged.

And when yet another new Texas constitution became law at the end of Reconstruction, in 1876, it was called the “Redeemer Constitution.” They got what they wanted. The term for the society they recreated was Jim Crow, the name of a black-faced minstrel, but it was, more accurately, apartheid: a segregated, authoritarian, racial caste system of terrorism anchored by paternalism and White male supremacy. It was a return of the antebellum world, enforced by outlaws and hooded vigilantes like the Klan to enforce its rules. Women were not even mentioned in the new Texas constitution. African Americans were disfranchised again, as they had been before the 15th Amendment.

States controlled all aspects of voting, and the Texas Democratic Party enforced it. One historian has said that if Black men had been able to vote, the woman suffrage movement would not have been possible at all, because White men did not want any form of racial mixing, even at the voting booth. By 1902 Texas had legalized the White primary, meaning only White people could vote in it. And because Texas was a one-party state, that meant that the primary election was as good as the general election once votes were counted. In 1903, Texas legalized the poll tax. And the woman suffrage bill that finally passed the Texas Legislature in 1918 applied only to their right to vote in the primary.

The reality was that in Jim Crow Texas, White suffragists could not expect to get the vote for themselves if they supported suffrage for Black women or men. White women were excluded from party power, yes, but they still maintained their own power through racial superiority. They knew men in power--they were their friends, cousins, sisters, daughters, and wives. If they had any influence at all in convincing White males to legalize woman suffrage, they could not afford to antagonize them.

Part 3: What about Women of Color?

Having said all this, the fact that Texas was thoroughly segregated did not stop Black and Brown women from wanting the vote as much as White women did. But women of color were largely on their own when it came to winning the vote. They were at a very serious disadvantage.

Nevertheless, there are some things we know.

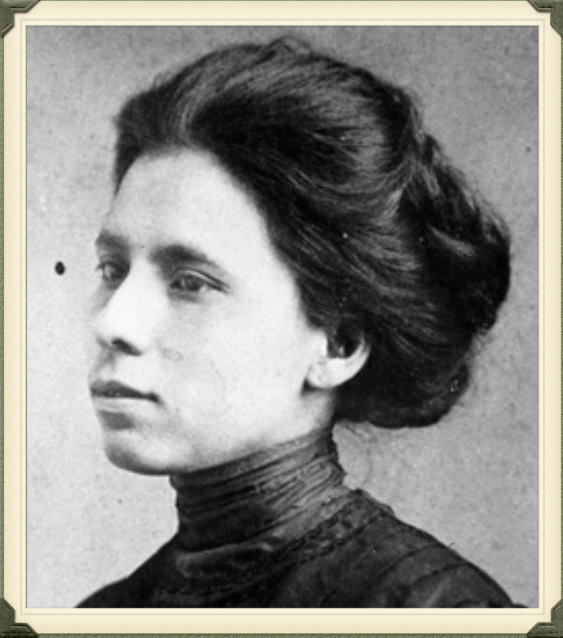

Tejana and African American suffragists in the early 20th century came from educated, middle class, urban backgrounds. They had progressive ideas about working with other women for social reform--what was later called  “civic housekeeping.” These Tejanas were from a class called gente decente, or decent people, and they had a tradition of forming women’s self-help groups called mutualistas. The best-known Tejana Progressive was Jovita Idar, a teacher and journalist from Laredo from a politically active, newspaper-owning family.

“civic housekeeping.” These Tejanas were from a class called gente decente, or decent people, and they had a tradition of forming women’s self-help groups called mutualistas. The best-known Tejana Progressive was Jovita Idar, a teacher and journalist from Laredo from a politically active, newspaper-owning family.

She wrote for her father’s paper, La Crónica, and joined with the family to create a conference in 1911 called El Congresso Mexicanista, which focused on ending the oppression of Mexican-heritage people on both sides of the Texas-Mexico border. One of the outcomes of this conference was the creation of a feminist group called La Liga Femil to advocate for women. Jovita Idar became its first president.

In 1914, she stood in the doorway of their newspaper to stop the Texas Rangers from shutting it down, on orders from the U.S. government, for having published articles critical of President Woodrow Wilson and the behavior of U.S. military troops on the border. The Rangers returned later. They destroyed the building and the equipment and arrested the workers.

In 1916, she and her brother, Eduardo, started a newspaper that supported woman suffrage and reported on suffrage activism in Texas and the nation. And she wrote for La Prensa, a newspaper in San Antonio, running pro-suffrage editorials and publishing the translation of a suffrage pamphlet produced by the Texas chapter of the National Woman’s Party.

Like Tejanas, African American suffragists knew that achieving the vote for women was just one of many civil rights reforms they needed. They knew well that Black men had won and then been deprived of the vote when Texas ignored the 15th Amendment. As a result, Black women were active in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). And, like Tejanas, they knew that getting woman suffrage in a deeply segregated state was a particularly difficult challenge.

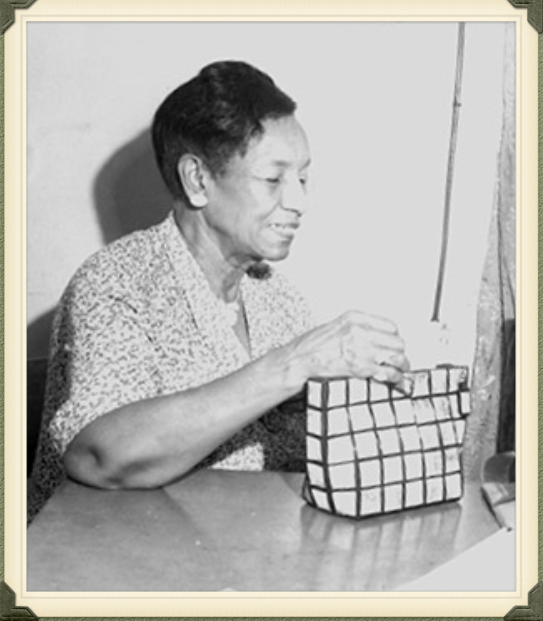

Nevertheless, Christia Adair worked with Anglo and Tejana suffragists in Kingsville when the Texas primary suffrage bill finally passed the Texas Legislature in 1918. This multi-racial cooperation was rare, but became possible in communities like Kingsville and El Paso where the population of Mexican-descent people was relatively high compared to other groups. Adair and other African American women tried to register and to vote in 1918 when White women voted for the first time, but they were refused by registrars who told them their skin was the wrong color. Adair’s response was to turn her energy toward the NAACP in Houston, which she did for the rest of her life.

Maude Sampson (later Williams) was the head of an African American suffrage group in El Paso who wrote to the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) in 1918 to request that her group become one of  its affiliates. Its head, Carrie Chapman Catt, knew that was not possible because the NAWSA was segregated. So she wrote to the head of the statewide Texas Equal Suffrage Association, Minnie Fisher Cunningham, and asked her to tell Sampson that she should not “embarrass” them by making the request. Cunningham did not go that far, but she did tell Sampson that her request would have to go through channels, which could not happen until much later, likely after the hoped-for 19th Amendment had already passed.

its affiliates. Its head, Carrie Chapman Catt, knew that was not possible because the NAWSA was segregated. So she wrote to the head of the statewide Texas Equal Suffrage Association, Minnie Fisher Cunningham, and asked her to tell Sampson that she should not “embarrass” them by making the request. Cunningham did not go that far, but she did tell Sampson that her request would have to go through channels, which could not happen until much later, likely after the hoped-for 19th Amendment had already passed.

Cunningham was a reform Democrat who might actually have welcomed the assistance of an African American club, but even had she wanted to, she could not have affiliated with Sampson’s club in Jim Crow Texas. White male legislators would have defeated any woman suffrage bill that would also have benefitted Black people.

In the end, Adair and Sampson achieved a significant victory anyway. Through their later work with the NAACP, they were involved in court cases that ultimately declared Texas’s White primary unconstitutional in 1944.

Understanding that all kinds of Texas women wanted the vote and worked for it requires that we reframe the woman suffrage movement with a wider, inclusive lens. The reason that White women were so visible in the historical record is that segregation and White supremacy forced women of color out of the picture. Worse, White women got the vote at their expense.

Now that we understand more about the national and state political context, and the situations of women of color, we can focus on the organized movement itself in Texas, knowing that it was run by White women for the benefit of White women.

Part 4: The White Texas Suffrage Movement

Progress in Texas toward woman suffrage was slow. Although the first time a bill supporting it in the legislature was 1868, the state was too big, rural, poor, and poorly educated for enough people to know or care about it. And most White women were likely more absorbed by recovering from the Civil War, grieving for their losses, rebuilding their homes and communities, and working toward spreading war memorials and statues glorifying the “Lost Cause” in cemeteries and public spaces through the United Daughters of the Confederacy, whose national chair for a time was a Texas woman.

Understanding of and support for woman suffrage did not begin to take off until the spread of railroads in the 1870s and 1880s, which contributed to urban growth that fostered better education and access to other resources. White suffragists used the railroads to take them to hard-to-reach small towns and isolated areas, causing grass-roots change.

A woman from Iowa named Mariana Folsom came to Texas in 1884 to work for suffrage, and she stayed until she died in 1909, riding trains to where ever she thought best, covering a geographic area in Central Texas from north to south and into East Texas, the Gulf area, and some of the Rio Grande Valley. She gave hundreds of speeches, and when she returned to a place, people put up posters announcing her talks.

As the Progressive movement spread, so did support for woman suffrage from groups like labor unions, the Grange, and the People’s Party. Women’s clubs were spreading, giving women the opportunity to meet with women of like minds about all kinds of topics. Through clubs, women learned from each other about a host of ideas like how to organize, advocate for issues, and speak in public, all of which were good talents for supporting a reform movement.

And then the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) came to Texas and showed women how the vote could magnify their voices in support of freedom from the abuse many of them suffered at the hands of alcoholic husbands. The national WCTU endorsed votes for women in 1888, which was a huge boost to the cause.

In 1890, a strong national suffrage organization (NAWSA, previously mentioned) formed from the union of the two groups that had split in 1869 to compete with each. The heads of this new group were Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, who brought their racist ideas with them. In 1893 the first statewide Texas association formed, but it fell apart for lack of effective organization. And then the first generation of suffragists started to die. Stanton died in 1902 and Anthony in 1906, without having achieved victory. The new head of NAWSA, Carrie Chapman Catt, carried on its segregated culture.

Meanwhile, in Texas, voting was filled with fraud. Only elite White males could vote their own minds. No women could vote. And although some African American males could vote in East Texas if the Republican Party still operated, the Democratic Party routinely stole votes and awarded them to their own candidates.

Mexican immigrants were allowed to vote if they applied for citizenship, even if they never became citizens. This fraud was made possible by a political machine of Rio Grande Valley ranch bosses who controlled the Mexican labor pool. They rounded up Mexican-descent workers and took them to the polls, paying their poll taxes, filling in their ballots, or in other ways assuring that these immigrants voted as the machine wanted them to.

This situation reveals clearly the benefit that White males enjoyed by controlling the voting system. It also revealed that there was value in votes to some audiences, and women began to see that they were competing with immigrants for the vote. They also understood they needed to offer something of value in return for the right to vote.

Eventually, Texas suffragists supported the disfranchisement of immigrant voters, using nativist and patriotic rhetoric about the superiority of White women who were already citizens. During World War I, in which Germany was the enemy, they also advocated the disfranchisement of German immigrants in Texas. Besides, they argued, even U.S. soldiers, including Texans, were disfranchised as soon as they donned their uniforms.

There was another, astonishing development that challenged suffragists. Between 1907 and 1922, just as the suffrage movement was heading into its final years, new laws stipulated that any native born or naturalized American female would, if she married a noncitizen, lose her own citizenship. Another aspect of the surge of nativism at this time, this national law revealed not only the high level of distrust of immigrant non-citizens, but also of the extent to which American women lost their identity with marriage and were assumed to do whatever their husbands told them, including how to vote. It is still unclear whether this law affected any Texas suffragists, but it did affect women involved at the national level.

Carrie Chapman Catt played the nativist card as well, deciding that what Texas needed was a socially acceptable, elite, White woman to become the head of the Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA), the new statewide organization. NAWSA was interested in getting states to show significant support for suffrage, hoping that a groundswell at the state level would assist in getting a federal suffrage amendment ratified. Catt was very interested in Texas for this reason, so she put effort into convincing the White power structure that Texas suffragists were not radicals, but the cream of the crop. Her Society Plan sought the “right” kind of women, middle- and upper-income Anglos with no controversies in their pasts, who were Democrats. Catt personally persuaded three Texas women, one after the other, to lead TESA. First was Annette Finnigan of Houston, then Eleanor Brackenridge of San Antonio, and third, Minnie Fisher Cunningham from Galveston, who took over TESA in 1915.

Cunningham was the most politically astute of the three. She came from an old plantation family and was well educated, if not wealthy. Her father had been in the legislature, and he had taught her about politics. Both of her parents had enlightened racial views, so she never joined the United Daughters of the Confederacy but became a reform Democrat and a Progressive. After the 1900 hurricane in Galveston, Cunningham had organized  women to find and distribute clean milk for children. She later liked to say that she had floated into the suffrage movement on a sea of bad milk.

women to find and distribute clean milk for children. She later liked to say that she had floated into the suffrage movement on a sea of bad milk.

In 1917, another resolution supporting woman suffrage in primary elections only came up in the legislature and, once again, died. This could have meant the end of the suffrage campaign, and Cunningham knew it, because the governor was James Ferguson, the corrupt, conservative Democrat who did not support woman suffrage and had said so loudly and derisively at the 1916 Democratic National Convention in St. Louis.

But Ferguson got himself in trouble when he launched a political attack on his perceived enemies at the University of Texas, including the president, and attempted to get them replaced with his own conservative friends. These people were among the suffragists and suffrage supporters whom Cunningham relied on, and with the help of a targeted professor, she and clubwomen around the state created the Woman’s Campaign for Good Government to inform people, including the university’s Ex-Students Association, about the Ferguson attack and to lobby the legislature for his impeachment. The plan worked, and who was waiting in the wings to become governor? The more moderate Lt. Governor, William P. Hobby.

Hobby was neither an advocate for nor an opponent of suffrage, which Cunningham considered an advantage compared with Ferguson. When Ferguson decided to run for governor again in 1918, Cunningham struck a bargain with Hobby. If he would resurrect the failed 1917 bill and get it passed, then newly enfranchised women would vote for him for governor instead of Ferguson. Hobby agreed. Then Cunningham made the same deal with a pro-suffrage, pro-Hobby leader in the Texas House, and he agreed.

The deal worked. The bill passed both houses, Hobby signed it, and White women in Texas finally had the right to vote in the all-White primary. Although there was much jubilation with the victory, there were only sixteen days left in which to register women to vote, which they had to do if they wanted to keep their part of the Hobby bargain. Suffragists mobilized all over the state and succeeded in getting 386,000 White women registered. And there was no internet then.

African American women and Tejanas tried to register all over the state, but they were turned away because they were not White. In the end, Hobby was elected governor because of the number of votes cast by those White women who had voted for the first time. Cunningham had known that powerful men would respond to offers that would benefit their own interests, and she had found the perfect bargaining chip: the governorship.

She also knew, once that was achieved, that voting women finally held their own political power. So in 1919, when the 19th Amendment came up in Congress for a vote, she knew that women had an opportunity. Suffragists launched a letter-writing campaign to the Texas delegation reminding them that Texas’s new female voters supported passage of the Amendment and that they would be watching. The delegation voted for the amendment, and it passed both houses, moving on its way to the states for ratification.

For his part, Gov. Hobby understood that he owed a debt, not only to Cunningham for her role in getting Ferguson impeached and making him governor, but also to Texas women for electing him in his own right. When the time came for Texas to ratify the 19th Amendment, Hobby made certain that happened, and Texas became the ninth state in the U.S. and the first southern state to ratify it. When the required number of remaining states finally ratified it, the 19th Amendment became a part of the U.S. Constitution on August 26, 1920.

Part 5: The Dangerous State of the Vote Today

As great a victory as this was, over 70 years after the Seneca Falls Convention, and over 50 years after woman suffrage was first considered in Texas, the 19th Amendment still did not give all women the right to vote. Why? Because states still controlled elections, and in Texas, only Whites could vote. During all the years between 1920 and 1965, people of color continued to have their voting rights denied, not only by states like Texas, but also in Congress, where segregationist Democrats, called Dixiecrats, wielded enormous power, and they would not budge on civil rights.

Even Franklin Roosevelt did not support anti-lynching legislation because he needed Dixiecrat votes for his New Deal bills. Not until Harry Truman insisted on integrating the military in the late 1940s did things slowly begin to change. Eventually, with the spread of the Civil Rights movement, more moderate Democrats like Lyndon Johnson began to support such rights. In 1964, President Lyndon Johnson succeeded in passing and signing the Civil Rights Act. And in 1965, after the horrific events on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, when horse-mounted and truncheon-carrying police brutalized marchers demanding equal rights, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act.

People of color could vote after 1965 because southern states no longer had total control over elections. They now had to have their procedures vetted by the federal government to assure they were race neutral. The Voting Rights Act worked as it was intended until 2013, when the Supreme Court decided that federal oversight was no longer needed, and it gutted that part of the act. The stories we have seen since then, about southern states purging voter rolls and closing polling places and intimidating voters of color are a result of this decision. The U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill in 2020 to reinstate those requirements. It sits today in the Senate without action taken.

So here we are, 100 years in, and the suffrage story remains unfinished. Once again, not all women, or all men, can vote, and the suffrage movement itself, writ large, is still not over.

Further Reading

Acosta, Teresa Palomo and Ruthe Winegarten. Las Tejanas: 300 Years of History (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003).

Boswell, Angela. Women in Texas History (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2018).

Brannon-Wranosky, Jessica. “Mariana Thompson Folsom: Laying the Foundation for Women’s Rights Activism,” in Texas Women: Their Histories, Their Lives. Ed. by Elizabeth Hayes Turner, Stephanie Cole, and Rebecca Sharpless (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015).

_____. “Southern Promise and Necessity: Texas, Regional Identity, and the National Woman Suffrage Movement, 1868-1920,” dissertation, University of North Texas, 2010.

Campbell, Randolph B. An Empire for Slavery: The Peculiar Institution in Texas 1821-1865 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1989).

Cantrell, Gregg. “‘Our Very Pronounced Theory of Equal Rights to All’: Race, Citizenship, and Populism in the South Texas Borderlands,” Journal of American History, December, 2013).

_____. The People’s Revolt: Texas Populists and the Roots of American Liberalism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020).

González, Gabriela. “Jovita Idar: The Ideological Origins of a Transnational Advocate for La Raza,” in Texas Women: Their Histories, Their Lives. Ed. by Elizabeth Hayes Turner, Stephanie Cole, and Rebecca Sharpless (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015).

Gordon, Ann D., ed. African American Women and the Vote, 1837-1965 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1997).

Graham, Sara Hunter. Woman Suffrage and the New Democracy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996).

Gunter, Rachel M. “‘Without Us, It is Ferguson with a Plurality’: Woman Suffrage and Anti-Ferguson Politics,” in Impeached: The Removal of Texas Governor James E. Ferguson. Ed. By Jessica Brannon-Wranosky and Bruce A. Glasrud (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2017).

_____. “More than Black and White: Woman Suffrage and Voting Rights in Texas, 1918-1923,” dissertation, Texas A&M University, 2017.

_____. “Immigrant Declarants and Loyal American Women,” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era (August, 2020).

Humphrey, Janet G., ed. A Texas Suffragist: Diaries and Writings of Jane Y. McCallum (Austin: Ellen C. Temple, 1988. Reprinted, College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2015).

Laumen, Lauren Ashley. “‘Womanly Women’: The Antisuffrage Movement in Texas, 1915-1919,” thesis, Texas Christian University, 2005.

Masarik, Elizabeth Garner. “Por La Raza, Para La Raza: Jovita Idar and Progressive-Era Mexicana Maternalism along the Texas-Mexico Border,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly (January, 2019).

McArthur, Judith N. and Harold L. Smith. Minnie Fisher Cunningham: A Suffragist’s Life in Politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

_____. Texas Through Women’s Eyes: The Twentieth-Century Experience (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010).

_____. “Not Whistling Dixie: Women’s Movements and Feminist Politics,” in The Texas Left: The Radical Roots of Lone Star Liberalism. Ed. by David O’Donald Cullen and Kyle G. Wilkison (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2010).

Moyer, Elaina Friar. “Claiming Space in the Suffrage Movement: The National Woman’s Party in Texas, 1915-1920,” thesis, Texas A&M University Commerce, 2018.

Pitre, Merline. “Texas and the Master Civil Rights Narrative: A Case Study of Black Females in Houston,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly (October, 2012).

Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn. African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850-1920 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998).

Tetrault, Lisa. The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1848-1898 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

Torget, Andrew J. Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800-1850 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015).

Winegarten, Ruthe and Judith N. McArthur, eds., Citizens at Last: The Woman Suffrage Movement in Texas (Austin: Ellen C. Temple, 1987. Reprinted, College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2015).